My grandfather was a member of the Holy Anna of Novgorod Orthodox Congregation. He was 90-years-old before my family found that, within the Orthodox Church, he was not called Bo, but Andrew (Andreas), after the saint. This work is about the obstacles that occur when I paint an icon. I paint the Apostle Andrew. I wrap the icon in fabric, create a wooden container. I close the lid. In this way the icon will keep a hope of living.

In March 2018 I wrote a letter to my grandfather. He had then been dead for over a year. The Christ Pantocrator icon, painted by Timotije Kosanovic, was by his side when he passed (a Swedish version of the letter comes at the end):

Dear grandfather,

I remember something you said. Not word for word, but I remember the tone. As if it was important that you told me before I would say too much:

– No, you cannot do that!For a year, I had tried to understand the foundation of icon painting and I wanted to tell you about my attempt to paint myself. I understood that I had no right and left it hidden in the bag.

Remember when I told you that I was going to write about icons and you gave me a reproduction of your Christ Pantocrator? You mounted it on a wooden panel with red-painted sides. Then I could come close to the original you thought. Am I wrong to claim that a reproduction cannot reveal if the original lacks an inner truth? That its own life cannot be determined?

The icon is a witness and is in direct contact with the person it depicts. My communication has shortcomings. I paint without right. It is the apostle Andrew, the first called. You were 90-years-old before we were told you went under this name in your congregation.

In the meeting with the icon, the individual has no space. Without its true context, it would die. So, I wrap my icon, put it in a box and attach the lid. Invisible it retains the hope of living. I achieve something. But then comes doubt. Have I created a mirage, a dream of what I never managed to transcend?

…..

Since you passed, I have thought about your loneliness. I have thought about the church as a room of comfort, where you can be abandoned in the company of others. Am I disrespectful when I put this in relation to your way of searching for a sense belonging? To be truthful, you were never a great family father. Instead, you set up another universe of affinity, your art historical archive.

You return to the room where everything comes naturally. Through a magnifying glass the light table illuminates an image and you formulate your coming assignments. This is life itself. You let yourself be absorbed. All energy is directed towards this.

I watch over you when you die. You are filled with death fear during your final hours and I see how life releases your body, undignified. To be mortal is lonely and in loneliness there is a desire to be whole. So, I ask that your icon of Christ Pantocrator will be placed in your bed. You put the back of your hand against the gold leaf and take a final breath.

Now I have to do what I cannot do. And I hope you will see how uncertainty can be fruitful. It’s on this your conviction rests. We are similar in many ways.

Warm regards, Ida, Stockholm, March 31, 2018

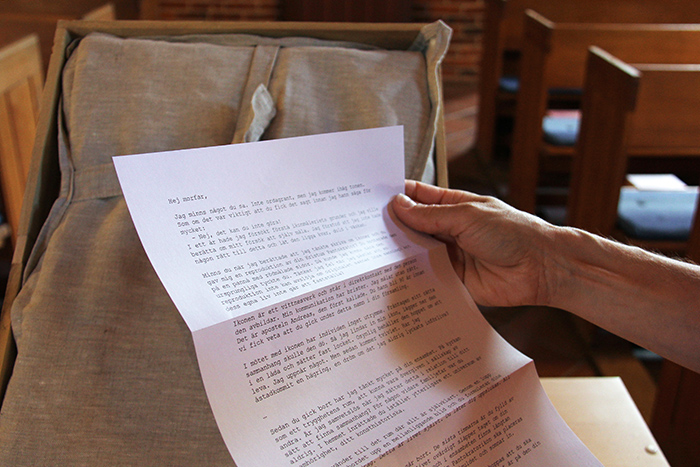

Hej morfar,

Jag minns något du sa. Inte ordagrant, men jag kommer ihåg tonen. Som om det var viktigt att du fick det sagt innan jag hann säga för mycket:

– Nej, det kan du inte göra!I ett år hade jag försökt förstå ikonmåleriets grunder och jag ville berätta om mitt försök att själv måla. Jag förstod att jag inte hade någon rätt till detta och lät den ligga kvar, dold i väskan.

Minns du när jag berättade att jag tänkte skriva om ikoner och du gav mig en reproduktion av din Kristus Pantokrator? Du monterade den på en pannå med rödmålade sidor. Då kunde jag komma nära den ursprungliga tyckte du. Tänker jag fel när jag påstår att en reproduktion inte kan avslöja om originalet saknar inre sanning? Att dess egna liv inte går att fastställa?

Ikonen är ett vittnesverk och står i direktkontakt med den person den avbildar. Min kommunikation har brister. Jag målar utan rätt. Det är aposteln Andreas, den först kallade. Du hann bli 90 år innan vi fick veta att du gick under detta namn i din församling.

I mötet med ikonen har individen inget utrymme. Fråntagen sitt rätta sammanhang skulle den dö. Så jag lindar in min ikon, lägger ner den i en låda och sätter fast locket. Osynlig behåller den hoppet om att leva. Jag uppnår något. Men sedan kommer tvivlet. Har jag åstadkommit en hägring, en dröm om det jag aldrig lyckats införliva?

…..

Sedan du gick bort har jag tänkt mycket på din ensamhet. På kyrkan som ett trygghetens rum, att kunna vara övergiven i sällskap av andra. Är jag samvetslös när jag sätter detta i relation till ditt sätt att finna sammanhang? För någon vidare familjefar var du aldrig. I hemmet inrättade du istället ytterligare ett universum av samhörighet, ditt konsthistoriska.

Du återvänder till det rum där allt är självklart. Genom en lupp lyser ljusbordet upp en mellanliggande bild och du formulerar dina kommande uppdrag. Detta är livet självt. Du låter dig uppslukas. All energi riktas hit.

Jag vakar över dig då du går bort. De sista timmarna är du fylld av dödsfruktan och jag ser hur livet ovärdigt släpper taget om din kropp. Att vara dödlig är ensamt och i ensamheten finns längtan efter att vara hel. Så jag ber att din Pantokratorikon ska placeras i din säng. Du lägger handryggen mot bladguldet och somnar in.

Nu måste jag göra det jag inte får göra. Och jag hoppas att du ska kunna se hur osäkerheten kan vara något fruktbart. Det är på den din övertygelse vilar. Vi är på många sätt väldigt lika.

Varma hälsningar Ida, Stockholm den 31 mars, 2018

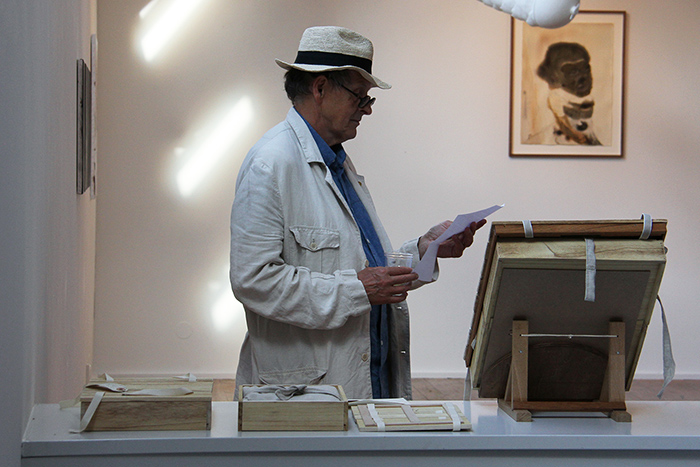

Images from the exhibition “Helighetens Bilder”, at the Francis Chapel in Nyköping, Sweden, June 2018: